We need to tackle bad science head-on, argues Roger Watson.

Until the appearance of the novel coronavirus, subsequently known as Covid-19, few will have been aware of a tiny group who refer to themselves as ‘virus sceptics’. They eschew the label ‘virus deniers’, despite challenging established scientific orthodoxy regarding the existence of viruses. Leading contemporary exponents of virus scepticism include New Zealand doctors Mark and Sam Bailey, British nurse Dr Kevin Corbett and United States doctors Andrew Kaufman and Thomas Cowan.

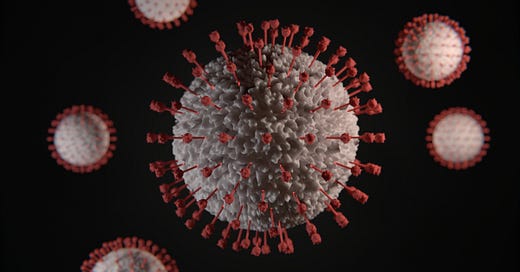

Most lay people have little idea what a virus is, despite probably having succumbed to several viral infections in their life, principally cold and influenza and, more recently, Covid-19. A virus is a particle composed of the template of life – the genetic material nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) – around which is wrapped a protein coat. Viruses exist in a twilight zone between being organisms and simply being inert nucleoprotein complexes. They are incapable of reproducing themselves, they depend on being able to enter host cells and the proteins in viruses help them to attach to and enter them. Host cells can include both animal and plant cells.

What is a virus?

Viruses exploit the genetic processes of the cells they infect. Specifically, they must make use of what is referred to as the central dogma of genetics, a process whereby DNA provides a template for the synthesis of RNA which subsequently provides a template for protein synthesis. Proteins are responsible for all the structural and synthetic processes of cells which enable whole organisms, such as the human body, to function.

Viruses may contain either type of nucleic acid: DNA or RNA. If they contain the former, once introduced to cells their DNA becomes integrated into the DNA of the host cell. They hijack the synthetic processes of the host cell to make more copies of the virus. If they contain RNA, then this is not capable of being integrated into the DNA of the host cell. They either use their RNA directly to make other copies of the virus or, with the help of an enzyme known as reverse transcriptase, they can reverse the central dogma of genetics and make DNA which is subsequently integrated into the host cell DNA and used to make copies of the virus. Once sufficient viral particles have been made the host cells will burst, releasing the viral particles which then infect further cells and the process continues until the body has managed to stop this process or, in severe cases, death ensues.

The ill effects we suffer when we become infected by a virus are a result of our immune system trying to neutralise the virus and the toxic substances being released from damaged cells. These include the classic signs of infection resulting from the action of the immune system: pain, fever and tiredness. There is no ‘cure’ for a viral infection and usually symptoms such as pain and fever are dealt with symptomatically. Some antiviral drugs (not without their side effects) exist but are not used routinely and vaccines (also not without potential harms) are effective against some viruses.