When civilisation is held in contempt, few will feel compelled to save it from destruction, writes Joanna Williams.

In 1666, as fire raged across London, booksellers dragged their stock to St Paul’s Cathedral. They hoped that in the safety of the crypt, books would be spared the flames. Tragically, the intensity of the fire caused the lead roof of the cathedral to melt ‘as if it had been snow before the sun’ (1) which, in turn, meant ‘the weighty stones falling down broke into the vaults and let in the fire, and there was no coming near to save the books.’ (2)

Books thought to be worth £17million in today’s money were destroyed along with the magnificent cathedral itself. But, as those seeking a refuge for their stock knew all too well, no price could be put on the history, wisdom and beauty that dissolved into ash.

Almost 300 years later, St Paul’s was once more at risk of burning. With its iconic dome, the cathedral became a focal point for the Luftwaffe, guiding pilots on bombing raids into the heart of the City of London. St Paul’s was of symbolic as well as strategic significance. By withstanding bombardment all around, the cathedral came to represent ‘the steadiness of London’s stand against the enemy: the firmness of Right against Wrong’. A photograph of St Paul’s dome, proudly intact despite the surrounding devastation, was described as a symbol of ‘the indestructible faith of the whole civilised world’.

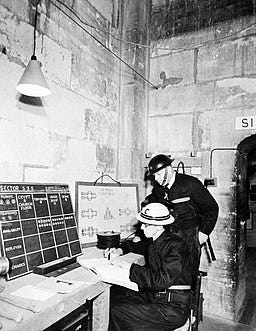

The brave men and women of St Paul’s Watch ensured the cathedral survived the Blitz. This volunteer fire brigade, comprising over 300 people drawn primarily from clergy, church staff and local residents, kept vigil every night of the war. Its members watched for bombs hitting the building in order to put out fires before they had chance to spread. By the end of the war they had extinguished fires from more than 60 bombs and and saw the cathedral survive two direct hits by high explosives. Thanks to their efforts, St Paul’s remained standing.

St Paul's Fire Watch

Exhausted volunteers were driven to stand guard night after night because St Paul’s was more than just a building. With its history, architecture and beauty, and through serving as the final resting place for so many great figures from Britain’s past, St Paul’s Cathdral came to represent civilization itself. The Watch’s efforts were a testament not just to their faith in God but to their belief in man’s incredible potential for good. To save St Paul’s was to preserve the best humanity had accomplished.

Sadly, we might struggle to find volunteers motivated to go to such lengths to preserve a monument to civilization today. Rather than celebrating humanity’s potential for beauty, wisdom, ingenuity and bravery as expressed through great works of art, literature, architecture, scientific discoveries, musical scores or monuments to past heroes, we are taught to see the past as tainted. Far from wanting to revere key figures in our nation’s past, leading cultural commentators seek to kick away the pedestal and expose individual frailty alongside mankind’s collective sin. Rather than preserving civilization we are encouraged to tear it down.

Public statues and monuments to historical figures have become a particular target for those seeking to tear down, rather than preserve, civilization. When the past is judged by the moral standards of the present, no one emerges unscathed. Not just in Britain but around the world, statues have been removed, vandalized, or ‘contextualized’ with scripts detailing a litany of sins. In Bristol, a statue of merchant, philanthropist and slave trader Edward Colston was toppled and dragged through the streets before being dumped into the harbour in an outburst of rage directed at an inanimate object. In Australia, statues of Captain Cook and in the US, statues of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson have all met a similar fate.

As I explore in Teaching National Shame, tearing down statues does not necessarily cause a disregard for history or a disrespect for historical figures and their achievements. More, these are actions that arise within societies that have already come to view the past with suspicion. We see this unease on display with attempts to re-write history itself. The 1619 Project, established by the New York Times, seeks to ‘reframe’ America’s history by making the ‘consequences of slavery’ and ‘white supremacy’ the ‘dominant organizing themes’. At a stroke, all that is progressive and inspiring about the history of the US is erased. Meanwhile, in Australia, a campaign to change the date of Australia day from 26th January, the date that the first fleet of British settlers arrived on the island, is gaining momentum. Shame about national history makes it far more difficult for people to revere the cultural legacy of the past.

In schools and universities, the demand to ‘decolonise the curriculum’ drives identity politics into the heart of education by insisting that all human knowledge and creativity is assessed according to the skin colour, gender or sexuality of its author rather than its intrinsic value. Again, we see that culture - particularly historical products of white, western culture - are treated with particular suspicion. What begins as a relativist call to expand curricular content to cover a broader range of identity groups, rapidly morphs into an assault on the historical legacy of the canon, a de-centering of western knowledge, and an attack on enlightenment values of reason, rationality and universal humanity. Students are left with little more than contempt for the cultural and intellectual legacy of such a tradition.

When the past is presented as problematic at best, sinful at worst, we inculcate a suspicion for its intellectual and artistic accomplishments in younger generations. If not actively torn down and destroyed, they are passively left to gather dust and, eventually, forgotten. We face either contextualised culture, art so heavily caveated it can never be enjoyed for its own sake, or a Year Zero approach to civilisation itself where everything before the present is to be erased from memory.

When civilisation is held in such contempt, who will feel compelled to save it from destruction?

Towards the end of my recent visit to St Paul’s, my friend Lisa VanDamme - who had encouraged me to make the tour in the first place - reminded me of Florence’s Mud Angels. In November 1966, the River Arno broke over its banks and flooded Florence. Enormous quantities of mud were deposited across the city, building up huge mounds within buildings including churches, museums, art galleries and libraries. The city’s artistic and historical treasures risked devastation. But something remarkable happened. Young people from across Italy and the rest of Europe left work or university and traveled to Florence to help rescue the city. They became known as gli angeli del fango, or ‘the Mud Angels’. Throughout the whole of that winter, these young volunteers ‘cleaned mud out of the Basilica di Santa Croce, carried priceless paintings out of the Uffizi galleries and brought food and fresh water to the elderly Florentines trapped in their upper-floor apartments.’

The Mud Angels recognised that something was worth saving in Florence’s art galleries and museums. The books, paintings and sculptures may have been old. They may have been created by white men. But they possessed a beauty that transcended the circumstances of their creation. Florence’s cultural artefacts were worth saving, just as St Paul’s had been worth saving, because they represented civilization itself.

Raga Salvatore, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sixty years after the Mud Angels and 80 years after the Blitz, too many young people are left alienated from the cultural legacy of their own society. They have been informed that works of art are hopelessly problematic products of their time - most likely racist, sexist, homophobic and transphobic - long before ever having had an opportunity to fall in love with the best that humanity can create. It is hardly surprising, then, that rather than celebrating beauty, wisdom, ingenuity and bravery as expressed through great works of art, literature, architecture, scientific discoveries, musical scores or monuments to past heroes, such objects are no longer deemed worthy of the investment of time and intellect necessary for their appreciation.

We need to change the conversation. Rather than asking what must be torn down, trashed, contextualized, decolonized, or ignored, we need to ask what is worth preserving. Rather than asking what books should be removed from libraries, or what art should be taken off gallery walls, we need to ask what best embodies beauty and humanity’s potential for good. Rather than cultivating cynicism, we need to show young people the best that civilization has to offer.

Who will join the St Paul’s Watch or Mud Angels of tomorrow? And what will they preserve?

Joanna Williams is the Director of Cieo and the author of How Woke Won.