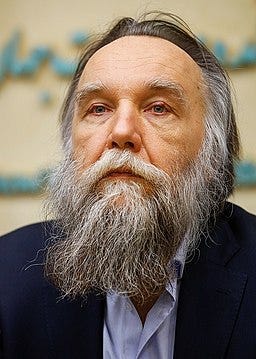

The killing of Darya Dugina, daughter of Russian nationalist ideologue Alexander Dugin, has raised questions about her father – seemingly the intended target of the attack. Just who is Alexander Dugin and what is his influence on Putin, asks David Martin Jones.

Darya Dugina was a journalist and vocal supporter of the war in Ukraine, yet it seems certain that the car bomb that led to her death earlier this week was not intended for her, but for her father: Alexander Dugin. His attempted assassination has drawn attention to the role his thinking plays in Putin’s Russia. But who is Dugin? And what exactly is the political philosophy animating Russia’s bid to regain lost territories?

Alexander Dugin emerged in the 1990s as Russia’s most influential exponent and interpreter of the Nazi legal expert and geopolitical strategist Carl Schmitt. In a number of books, Dugin adapted Schmitt’s fascist worldview to the current dilemmas of Eastern Europe. In the process he has given intellectual and strategic depth to Putin’s thinking on rectifying the trauma that the dismemberment of the Soviet Union caused between 1990-1996.

A philosopher and mystic, Dugin’s writings advocate the unification of all Russian speaking peoples within a single, enlarged, political space, by force if necessary. He considers the revival of a Eurasian heartland to offer the concrete basis for building a new Russian Tsardom. To achieve this Russia must, according to Dugin, ‘defeat the maritime world exemplified by the United States’.

Dugin’s most widely known work The Fourth Political Theory (2009) offers a ‘conservative revolutionary’ ideology for a post-liberal age. His theory, he argues, transcends the failed dogmas of communism, liberalism, and, somewhat less certainly, fascism. Dugin offers instead an ethnically based, post-modern, Neo-Eurasian, alternative.

Politically understood, Neo-Eurasianism may be characterised as the latest non-liberal response to the inevitable conflict, that Schmitt first identified, between ‘tellurocracies’ (land powers) and ‘thalassocracies’ (sea powers) for the ‘nomos’ or control of the earth. In Dugin’s version, Russia replaces Germany as the Reich (Empire) and Eurasia is its Grossraum or the pivotal power within an enlarged territorial space. Russia’s historic mission is both to promulgate the ‘political idea’ necessary to unify its Grossraum and decide upon its external relations with other Grossraum like the United States, China and Europe.

The Great Space

Dugin considers these great territorial spaces on the world continent, or world island, that stretches from Amsterdam to Shanghai, as a unification between themselves as geographical units and ‘the narodni’ (the people). This new order will be ‘built on historical kinship’ and ‘common fate’. Indeed, for Dugin, the political ideal of the Great Space reflects the homogeneity of its narod. Thus Neo-Eurasianism promotes a positive attitude toward the native population. By contrast, liberalism is considered to be ‘entirely incompatible’ with nativism and ethnocentrism. Ironically, this view finds affinity with identitarian movements across Europe and particularly with the Nouvelle Droit (New Right) thinking of Alain de Benoist in France.